If you're a new parent just now hearing about the term "unschooling", or a long-time unschooler just wanting some validation; if you're a parent whose kids' friends are unschoolers, or a teacher who has just quit working to unschool their kids (surprisingly common!), or a teacher who just welcomed former unschoolers to a classroom, this is for you. If you're an educator, a parent, a grandparent or a friend with concerns about some unschooled kids you know, this is for you, too.

This list includes many misconceptions that I held, myself, before unschooling and in the first few years of it. Unschooling is a learning curve for the whole family (and community!), and there is no shame in discovering that some beliefs we held were wrong. I'm proud of my growth in understanding, and know I still have plenty to learn.

And to be perfectly clear, I KNOW that if you're reading this with concerns for kids, those concerns are rooted in love. You adore those kids and you feel they deserve the best. Unschooling isn't always the best, but for many, it is. And I hope this article will not only set your mind at ease, but also inspire some further research, because the foundational concepts of unschooling are valuable for everyone, in every community, in every educational philosophy.

First, a brief primer:

What is Unschooling?

"Unschooling is an informal learning method that prioritizes learner-chosen activities as a primary means for learning. Unschoolers learn through their natural life experiences including play, household responsibilities, personal interests and curiosity, internships and work experience, travel, books, elective classes, family, mentors, and social interaction. Often considered a lesson- and curriculum-free implementation of homeschooling, unschooling encourages exploration of activities initiated by the children themselves, under the belief that the more personal learning is, the more meaningful, well-understood, and therefore useful it is to the child. While unschooled students may occasionally take courses, unschooling questions the usefulness of standard curricula, fixed times at which learning should take place, conventional grading methods in standardized tests, forced contact with children in their own age group, the compulsion to do homework regardless of whether it helps the learner in their individual situation, the effectiveness of listening to and obeying the orders of one authority figure for several hours each day, and other features of traditional schooling.

"The term unschooling was coined in the 1970s and used by educator John Holt, who is widely regarded as the father of unschooling. Unschooling is often seen as a subset of homeschooling, but while homeschooling has been the subject of broad public debate, unschooling received relatively little media attention and has only become popular in recent[may be outdated as of April 2023] years."

Wikipedia, May 26, 2023

|

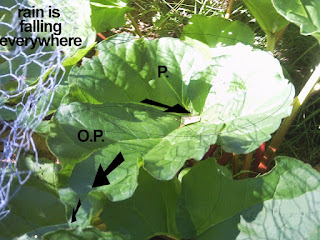

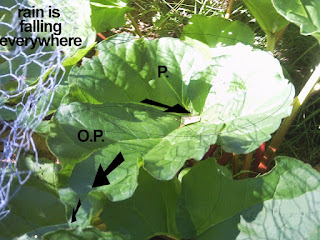

diagram of rhubarb, by Rhiannon, age 10

|

If you haven't read about unschooling before, and find this perplexing or fascinating, you may want to click through to Wikipedia and read the whole article. It's great! Or read books and articles by John Holt. And consider how each of those many ideas applies to our lives and upbringing as humans on this earth. Or as animals. Or as plants. My daughter, at age ten, wrote

a blog about gift economies, which was her passion at the time, and she noticed that rhubarb plants were funnelling rain water for themselves, while also redirecting a certain percentage to the ground (and other plants) around them--they were sharing! Because it was good for their shared ecology and future! I am still amazed by the connection she made, and by the extrapolation from humans to plants. The basic concepts of unschooling are like this, too: we can extrapolate these ideas to every aspect of our lives, communities, and ecologies and benefit.

So what are the myths?

Oh, there are plenty... here's my non-exhaustive list of top myths and misconceptions. Some are harmful to our kids' growth and lives in community, some prevent our kids from participating in activities with their friends, and some prevent non-unschooled kids from accessing the same benefits as unschooled kids do. Let's debunk these things so we all can thrive! 💚

Unschooled Kids Are Disadvantaged, Can't Compete in the Real World, or Won't Thrive as Adults

In the last decade, academic research has finally begun to take stock of this issue, thanks hugely to Gina Riley and Peter Gray, and here's a list of papers for you: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-49292-2_9 And especially, this:

"A sample of 75 adults, who had been unschooled for at least the

years that would have been their last two years of high school, answered

questions about their subsequent pursuits of higher education and

careers. Eighty-three percent of them had gone on to some form of formal

higher education and 44 percent had either completed or were currently

in a bachelor's degree program. Overall, they reported little difficulty

getting into colleges and universities of their choice and adapting to

the academic requirements there, despite not having the usual admissions

credentials. Those who had been unschooled throughout what would have

been their K-12 years were more likely to go on to a bachelor's program

than were those who had some schooling or curriculum-based homeschooling

during those years. Concerning careers, despite their young median age,

most were gainfully employed and financially independent. A high

proportion of them-especially of those in the always-unschooled group-had

chosen careers in the creative arts; a high proportion were

self-employed entrepreneurs; and a relatively high proportion,

especially of the men, were in STEM careers. Most felt that their

unschooling benefited them for higher education and careers by promoting

their sense of personal responsibility, self-motivation, and desire to

learn."

For perspective, the tertiary education enrollment percentage in 2020 was 80% for Canada in 88% for the USA. (Worldbank data) So unschoolers fare about the same as conventionally-schooled kids as far as higher-education enrolment goes--possibly better, in fact, since this data came from 2015, and the World Bank data (from five years later), shows that enrolment has been increasing. It's also becoming much easier for unschoolers to be accepted to colleges and universities without the usual prerequisites, like highschool diplomas. What would the data tell us if it was all current?

But is tertiary education even necessary for success in adulthood? Unschoolers are questioning this, too. In his article, Survey of Grown Unschoolers III: Pursuing Careers, Peter Gray states that his study "found that most [surveyed unschooled adults] have gone on to careers that are extensions of interests and passions they developed in childhood

play; most have chosen careers that are meaningful, exciting, and

joyful to them over careers that are potentially more lucrative; a high

percentage have pursued careers in the creative arts; and quite a few

(including 50% of the men) have pursued STEM careers."

Of course Gray's article considers both those who attained tertiary education and those who did not, but nearly twenty years of unschooling has shown me that unschooling makes kids particularly skilled at creating meaningful careers via non-traditional avenues, as well as resourceful, in living within their means, finding growth, discovery, and income in unexpected places. The mechanism that promotes this resourcefulness is exploration. Kids who grow up with not only freedom but also the necessity of finding their own paths learn experientially how to make the best of all situations. Most situations aren't managed or directed for them, so they learn to do these things for themselves, often at an earlier age than schooled kids, for whom the path was determined by someone else, and groomed by the thousands or millions of students who walked it, before.

Kids Need to Learn That Not Everything Is Going to Be Easy

There's an idea that school struggles (failure, bullying, unkind teachers, exhaustion, having to learn things when we don't want to) are helpful for growth. Yes, kids do grow from these experiences, but they're not real-world, and when we leave school we usually find ourselves in very different circumstances. Let's look at a couple of these things individually:

Social issues like unkind teachers and schoolyard (or in-class) bullying can be opportunities for learning to manage difficult situations--especially if there's support to do so. But in larger schools there is rarely support--if adults are even aware of the situation. Part of the reason my partner and I avoided sending our kids to school was that we were both relentlessly bullied throughout school, even sometimes while teachers were watching, and we were never helped. We didn't learn positive social skills from our many years of this experience. We learned not to trust figures of authority, or our peers. My partner learned to hide, and I learned to hate myself. This is not growth. We wanted something different for our kids, and we felt that giving them smaller groups with thoughtful adult oversight (as appropriate) gave them more opportunity to experience varied social situations and grow, without being permanently harmed. For the record, I'm not saying schools can't provide the support needed, but currently, by and large, schools are strapped for human and other resources, and not able to do so.

Having to learn when we don't want to might seem like a normal part of life, but after a couple of decades discovering explorative learning, I've seen that it's not helpful. Sometimes the obscure facts we had to learn in school become cemented later on, when the information becomes relevant, but if kids learn the things to begin with when it's relevant, it's cemented then. So there's nothing lost in not teaching things earlier. Sometimes, in fact, teaching things before children are developmentally ready to learn them, or when it's not yet relevant to their experience, we waste valuable time and energy that might have been used in more directly meaningful activities.

Also, unschooling is not easy. Unschooled kids encounter most of the same challenges that schooled kids do, but are encouraged to work out solutions for themselves, in their own ways, at their own pace. Life is still life, we still live, develop and learn to thrive in the same society, and learning is still learning. It's never easy.

Unschooling Is Only for People Who Can Afford to Stay Home with Their Kids

It breaks my heart to say this, but yes--it's partly true. Definitely in the early years, unschooling can be financially out-of-reach for single and/or low income parents. Also for parents without community support. School (and after-school programs) are a daycare system for many parents. In fact,

"John Foster (2011, p. 3) asserts that schooling ...tends to evolve in the direction of capitalist-class imperatives, which subordinate it to the needs of production and accumulation. He goes on to claim that public schools are more concerned with compliance and adherence to rules – skills needed for unskilled factory labor – and that a high quality education that focuses on leadership skills is reserved for children of America’s ‘governing class’ in private schools like Phillips Andover Academy (Bush’s alma mater) or Punahou School (Obama’s alma mater)."

~Schneller, Capitalism and Public Education in the United States

I don't have a handy quotation or data source for this, but am acutely aware that for our capitalist economy to function, most adults need to be working outside the home, consuming goods and paying, for most of their lives. The corporations (and elite) who own most of the wealth depend on the majority of the population to be working, in order to continue amassing that wealth. And from an individual middle- or lower-class perspective, the more this continues, the more we'll have to have two incomes just to afford food and shelter, so... schools that function as childcare are a necessity for survival. And survival is increasingly difficult for single parents.

If you're struggling just for food and shelter, you don't have time for stay-at-home-parenting, which is generally required for unschooling in the early years. There are, of course, quite a few families, who out of determination, desperation or luck, manage to work (and unschool) from home. Or who live in community or family situations that enable them to have free, exploration-friendly childcare, while they work. So it's not impossible, but you will never hear me say it's easy.

Unschoolers Are Privileged

Yes, my family is very privileged, not only financially, because my partner makes enough money to support us on his income alone, but also because we have the support of my parents, and because we're resourceful and happy to live with less than many. We did make sacrifices of time, experiences, and money in order to unschool. I also sacrificed what might have been the best years of my career. But I chose to have kids, and raising them to the absolute best of my ability was part of that, so these sacrifices are nothing in comparison to what we've gained. In fact, I don't think of them as sacrifices at all. That--the ability to see and value my privilege--is the greatest privilege I have.

But are we blind to our privilege? Are we greedy? I don't think so. Like many unschoolers, we work to help make unschooling an option for others, to bring the values of it into the community and into the public school systems, as much as possible. We work to promote the idea that freedom in learning and development can create wonderful communities and a prosperous future for humanity (especially in this time where many former careers are being handed over to machines, but that's another story). I think the greatest gift of having privilege is spreading it about. Like those rhubarb plants in my daughter's diagram: You take what you need, and share the rest around, because it's better for everyone in the end.

Unschooled Kids Are Smart. Most Couldn't Teach Themselves.

My kids are no smarter than other kids. They've just been given opportunities (freedom in life and education; time to explore) that many kids don't have, so they do things that seem impressive. They don't do these things because they're smart; they do these things because they had time and energy, while other kids were too busy.

I've often been told my kids have success because they learned things easily or "so early". No they didn't. They're about average. There's a lot that schooled kids will have been taught that mine never chose to learn. Like how to play football, or the plot synopses of hundred-year-old novels. Like calculus (my daughter) or mental math (my son, though despite this he studied calculus in college). Actually that's a great representation of the way unschooling looks, on paper: scattered. But in truth, while schooled kids often go through the expected routes to complete each step before moving on to the next, they also forget many of the things they were taught on those steps, and still end up in college calculus without being able to easily calculate thirteen minus five in their heads. That's why we have calculators. We access and use and forget and regain the tools we need as we need them. Unschooled kids are no different. Maybe they still learned about plot synopses, but it was because they were going through book reviews online, trying to find their next great read. Actually that might be how schooled kids ended up learning the same thing.

Also, all kids teach themselves. Or they "end up learning". Because learning is about discovery, and discovery comes from exploration, and it's in our nature to explore. From the moment babies discovered their first sensations in the womb, to the first time they discovered they could put their tiny premature thumbs in their mouths, to the moment they took their first steps and later made their first independent purchases, or partnerships... our kids have been exploring and learning all the time. The only difference with unschoolers is that they're encouraged to do so. (And in schools, the best teachers are facilitators of exploration.) The more opportunity kids have to explore and discover, the more they learn.

Unschooled Kids are Weird. And Antisocial.

I've heard this one so many times. Even from my kids' friends' parents. Maybe sometimes unschoolers are weird, but only because we're still in the minority. I'm the first person to admit that unschooling comes at a social cost. Not only because there are very few kids (especially in small communities like mine) who are available for social interaction on school days, but because we're often not welcomed by community programs, or other parents who are worried about exposing their own kids to unschoolers. Want to help? Welcome our kids! You'll get to know us and we'll all get more social interaction (and learning experiences!) It's that easy. 🙂

Unschoolers Are Radical Leftists, Communists, Conspiracy Theorists, Right-Wingers, Etc.

Nope. Well not more than in any community, anyway. We're just people trying to do the best we can for our kids. Unschooling is a radical choice in this stage of our culture's development, but that doesn't mean we're radical in other ways. Well actually... my regenerative garden is seen as radical, too, but I digress. And I suggest there are a lot of radical parents at every public school, as well, including unschoolers.

Unschoolers Don't Go to School!

Most unschoolers I know went to school at some point for a myriad of reasons. Mostly in lower grades because parents found it necessary for social or childcare reasons, and often in higher grades because the kids wanted to challenge themselves, to hang out with school-going friends, or to obtain some kind of diploma or degree. And unsurprisingly, there is a lot of crossover between education professionals (teachers, aides, tutors, mentors, advisors, and curriculum developers) and unschooling parents. What happens is that when you really learn a lot about how the education system works (and doesn't), and you're really committed to creating a better future for our society's children, you often end up looking into unschooling. If not for your own children, then for how you can implement its benefits in your classroom. As an unschooling parent and explorative learning educator, I've mentored various teachers on how to bring aspects of explorative learning (unschooling) into classrooms (and how to bring classes out of rooms--ha!) Unschoolers most definitely do go to school.

Unschoolers Miss Out on All the Classic Childhood Experiences

This one breaks my heart because in one very important way, it's true. Of course unschoolers usually miss out on classic childhood experiences, like high school grad (and elementary school grad, and kindergarten grad...), and that mean teacher that everybody loved to complain about, and the amazing school trips, and the sports they learned in gym class that most unschoolers don't ever learn.

I told myself that's OK because lots of kids miss out on expected traditions. As a parent wanting to have made the right choices for my kids, I reminded myself that millions of high-schoolers missed their grads because of COVID restrictions. Kids miss birthday parties because they're bullied and never invited. Kids miss out on sports because they were more interested in arts. Kids miss out on arts because schools aren't funded well enough to offer them... The list of things kids miss out on is endless. But that doesn't make the things unschoolers miss out on any easier on them.

The main thing unschoolers miss out on is a solid peer group. Especially in small communities like mine. No, it doesn't really matter that they missed out on the mean teacher or certain events. What does matter is that they weren't a part of the peer groups that experienced those. They lack the lexicon of all the mainstream kids; the inside jokes, the shared experience. In a big unschooling community this may not be an issue, but for my kids it was.

Of course, despite this, my kids chose to continue unschooling, for the benefits it afforded them. They did soften the social impact some by attending a democratic school for a few years, but it was in the big city, and we lived on an island, so on the whole their unschooled life still came at the cost of peers. I don't regret giving them the option of unschooling, but this is the only cost that has made me question my choices. The only solution I can see is time. Hopefully the increasing trends of explorative learning in schools as well as of unschooling in general will mean that in another twenty years unschoolers will have a big cohort with whom to share experiences and memories. That will be the way we heal this.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I think that's enough of my list. I hope this was enlightening, or comforting, or challenging, or whatever it is you need in your personal journey. I hope if you want to unschool your kids, this set some of your fears to rest. And I hope, like all of us, you keep exploring, discovering, learning, and enjoying the ride.

.jpg)

.JPG)